The United States government is shockingly tolerant of violence against the state. It has long encouraged violent insurrections against the government on just about every continent on earth. It has also condemned the violence and institutional political oppression deployed by world governments against their citizens, most recently in Iran for its recent crackdown on protestors and China’s dealing with citizens protesting Covid Zero policies.

As with anything regarding the United States, the contradictions are endless. In a statement by President Biden, the United States condemns Iran’s violence against peaceful protestors, but of course, the United States has both a long and recent history of doing just that. The US operates a political prisoner and torture facility in Guantanamo Bay yet they condemn Iran for imprisonment and torture, the United States has indicted citizens as terrorists for committing politically motivated property crimes, they decry China’s treatment of Uigyer Muslims yet they have the highest concentration of prisoners in the world despite having only a fraction of the world’s population - a disproportionate number of which are black and Hispanic.

The US is not wrong to condemn violence and oppression by the state, and of course, there is all sorts of justifiable violence against an oppressive government. It’s clear however that the US government is not centering violence in the context of ethics. What would logical consistency look like then? It would look a lot like amnesty for Assata Shakur.

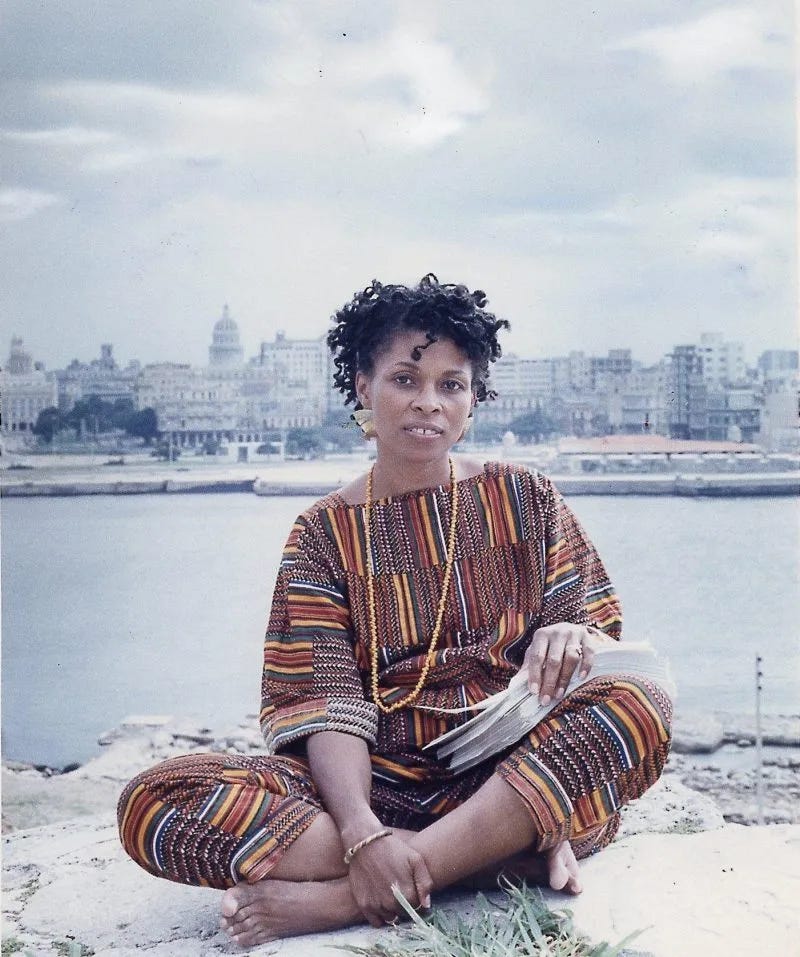

Assata Shakur is a black revolutionary currently living out her days in political asylum in Cuba after escaping a prison facility in the 1970s. The autobiography Assata documents much of her life as a young black woman in America, her revolutionary activities, and her life as what can only be described as a political prisoner.

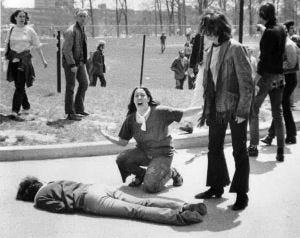

The United States of Assata Shakur’s youth was as racist and violent a country as you’d see being accused of such today. Preserving segregation, Jim Crow, and white supremacy with blood. The stories of her youth are rife with white mobs terrorizing her grandparent’s business, being thrown out of amusement parks for white children only, and watching a never-ending deluge of television where “black people were harassed and attacked”. Detailing what she saw happen on the news; “Martin Luther King’s house was bombed. Then came Little Rock. I can still remember those ugly terrifying white mobs attacking those little children who were close to my own age…And each year I would sit in front of that box, watching my people being attacked by white mobs, being bitten by dogs, beaten and water-hosed by police, arrested and murdered.”

The death and destruction wrought on people simply for looking the way she did, something Shakur describes as “the most primitive, reactionary, ignorant violence that exists”, created an extremism and revolutionary resistance movement that opposed the government. In one of her many sham trials, Shakur gave a speech to the jury so they might better understand the Black Liberation Army to which she belonged;

“The idea of a Black Liberation Army emerged from conditions in black communities: conditions of poverty, indecent housing, massive unemployment, poor medical care, and inferior education. The idea came about because black people are not free or equal in this country. Because ninety percent of the women in this country’s prisons are black and third world. Because ten-year-old children are shot down in our streets. Because dope has saturated our communities, preying on the disillusionment and frustration of our children. The concept of the BLA arose because of the political, social, and economic oppression of black people in this country. And where is oppression, there will be resistance. The BLA is part of that resistance movement.

While big corporations make huge, tax free profits, taxes for the everyday working person skyrocket. While politicians take free trips around the world, those same politicians cut back food stamps for the poor. While politicians increase their salaries, millions of people are being laid off. This city is on the brink of bankruptcy, and yet hundreds of thousands of dollars are being spent on this trial. I don not understand a government so willing to spend millions of dollars on arms, to explore outer space, even the planet Jupiter, and at the same time close down day care centers and fire stations.”

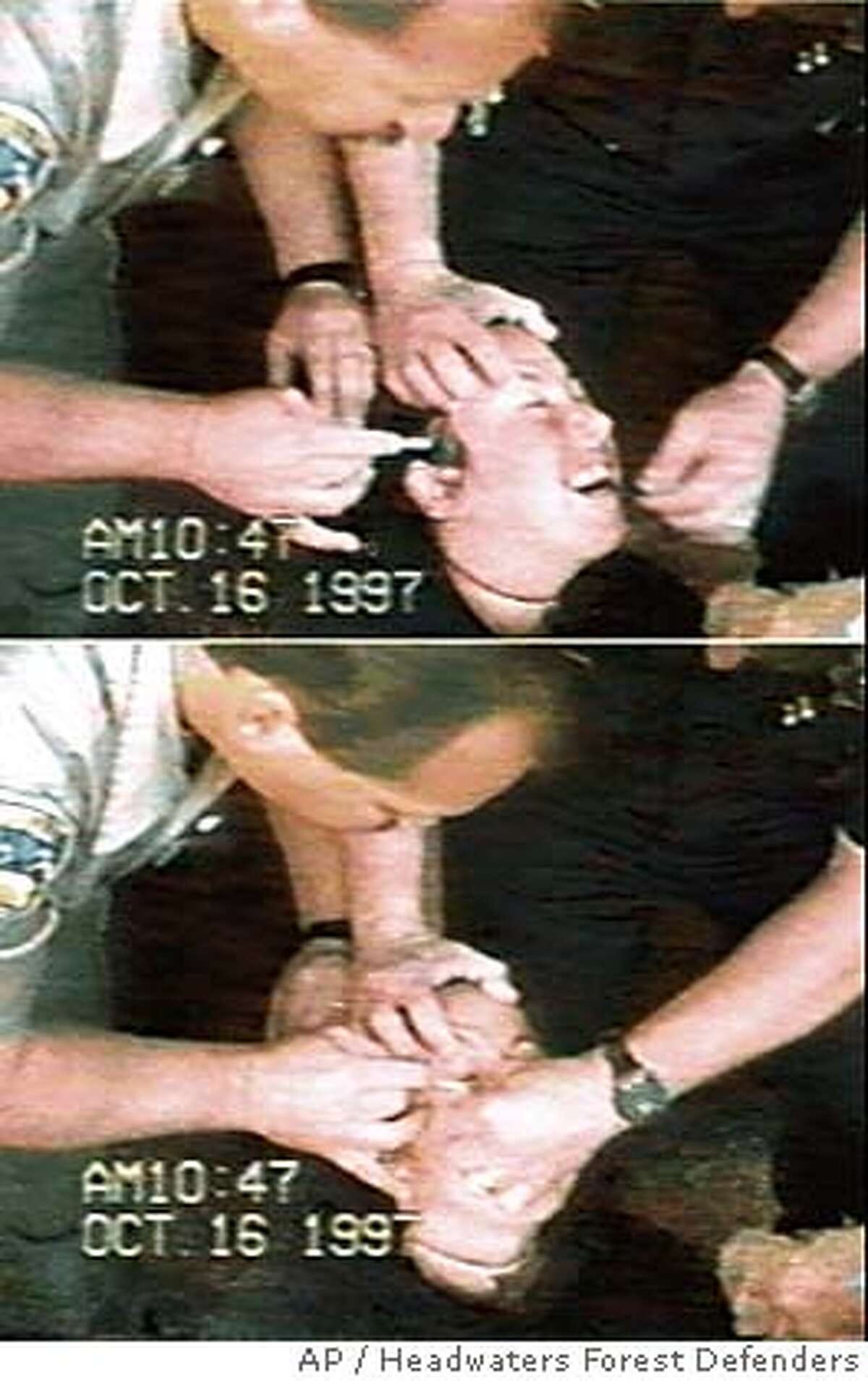

Throughout Assata, it’s clear that Shakur truly struggles with the more violent tendencies of this resistance movement. It took her a long time to join the Black Panther Party for this reason, but in the end, saw it was the only group adequately defending against the active brutality deployed by the United States government; “I was sick and tired of us being the only victims, and I didn’t care who knew it. As far as I was concerned, the police in the Black communities were nothing but a foreign, occupying army, beating, torturing, and murdering people at whim and without restraint. I despise violence, but I despise it even more when it’s one-sided and used to oppress and repress poor people.”

It’s clear that whatever violence she condones is of a defensive nature, not as an agent for the change she hopes to see. She’s clear that a revolutionary strategy must focus on mass movements, not military ones; “armed struggle, by itself, can never bring about a revolution…it must be part of an overall strategy for winning, and the strategy must be political as well as military.” Self-defense is the most justifiable of the whole spectrum of violence, yet simply embracing these tactics and beliefs made the entire organization a massive threat.

This is what ultimately made her and many other black revolutionaries a target of the United States government; Shakur did believe violence against a repressive state to be an inevitability. The sentiment that “nobody in the world, nobody in history, has ever gotten their freedom by appealing to the moral sense of the people who were oppressing them” was often shared in her circle. And while she felt that “a war between the races would help nobody and free nobody and should be avoided at all costs”, she also knew “ a one-sided race war with Black people as the targets and white people shooting the guns is worse. We will be criminally negligent if we do not deal with racism and racist violence, and if we do not prepare to defend ourselves against it.”

Sentiments like these made Shakur the target of the United States COINTELRPO program. She began to be viciously harassed and surveilled by the FBI and law enforcement. A common practice was to surveil a revolutionary, gather enough faulty “intel” to accuse them of a number of crimes, recklessly pursue and arrest them (ideally killing them in the process as they did to Fred Hampton), and then bank on racist courts and juries to pin them to a crime and get them locked in high-security prisons.

One might be inclined to think it stops there, however as Shakur notes; “in prisons, it is not at all uncommon to find a prisoner hanged or burned to death in his cell. No matter how suspicious the circumstances, these deaths are always ruled suicides. They are usually black inmates…among the most politically aware and socially conscious inmates in the prison”. If the arrest didn’t kill you, there was a good chance you could be taken out once in prison. A number of prisoners both notable and not have been killed this way. It’s a way to deploy the justice system as a more discrete instrument of murder since if the public sees someone in the process of the courts they’re less concerned than seeing them gunned down in the streets in cold blood.

Shakur herself was almost the victim of such a garish plot. She recounts that she would stack cups in front of the door of any prison cell she was stationed in when; “one night, in the middle of the night, the cups came crashing down. I immediately awoke to find four or five male guards standing in the doorway of my cell”. She was able to scream loud enough to dissuade the guards from doing anything. This was not the only time that police and guards tried to kill her. It’s worth noting here Shakur was never even convicted of a crime, she was simply being processed.

If it wasn’t an outright murder attempt, the prison conditions themselves were horrific. Solitary confinement was leveraged against Shakur without reason. International jurists from the United Nations Commission on Human Rights who were investigating prison conditions in the United States said “one of the worst cases is that of Assata Shakur, who spent over twenty months in solitary confinement in two separate men’s prisons subject to conditions totally unbefitting any prisoner.” From Shakur’s own words:

“If I wrote a hundred pages describing the basement of the Middlesex county jail, it would be impossible for you to visualize it. It was a big, grayish, pukey greenish cell. The ceiling was covered with all kinds of pipes, some small, some huge, some dry, some leaky. There was no natural light, and the jailers refused to open the small windows located near the ceiling. The average temperature was 95 degrees. It was infested with ants and centipedes.”

Assata Shakur was arrested on charges she was never guilty of, an arrest that almost killed her. She was then brutalized and stuck in solitary confinement for over a year of her life. She was deprived of her child and her loved ones were constantly being harassed. She is just one radical, there are countless others that suffered the same fate and whose stories may never be told. Hers is a crucial story told from beneath the hooves of the high horse upon which the United States rides around the world stage.

Remember the treatment of Assata Shakur and thousands of innocent black inmates at the hands of the US government, remember recent torture victims never accused of a crime, remember the sponsored bombing campaigns being undertaken against civilian populations the next time The United States Government seeks to condemn other nations for the same. The Declaration of Independence declares that “whenever any form of government becomes destructive…it is the right of the people to alter or abolish it, and to institute a new government”. The United States has justified many violent uprisings under this exact premise.

So considering this, if Assata Shakur’s only crime was opposing a government engaged in destructive behavior and escaping what was surely political imprisonment and torture, the United States can forgive these transgressions and issue a pardon to Shakur. Violence against the state is after all a hardened American value.

“I am about life…I’m gonna live as hard as I can and as full as I can until I die. And I’m not letting these parasites, these oppressors, these greedy racist swine make me kill my children in my mind before they are even born. I’m going to live and I’m going to love, and if a child comes from that union I’m going to rejoice. Because our children are our futures and I believe in the future and in the strength and rightness of our struggle.” - Assata Shakur

.jpg)