The Oxford English Dictionary of Philosophy seems to allude to the fact that the world of philosophy, for the most part, doesn’t really believe in free will. The school of thought that chocks free will up to an illusion is Determinism and apparently it is seen as a given. The only two schools that are allegedly held to challenge determinism are compatibilism and libertarianism (not to be confused with the political party, thinking, etc). Not only are these two schools relatively unpopular, they don’t even appear to believe in free will; they seem more concerned with the implications of responsibility. This, at best, maintains that free will is a useful illusion, but an illusion all the same.

It is the general, I-don’t-give-a-rip-about-academic-philosophy-public that perpetuates the specious illusion of free will. It is Sam Harris’ job in his essay, aptly titled Free Will, to dispel the beloved illusion. By my incredibly ammature standard he can only do this by making an argument people can follow, allaying any fears about the implications of dropping the illusion, and by writing a book people will generally want to read.

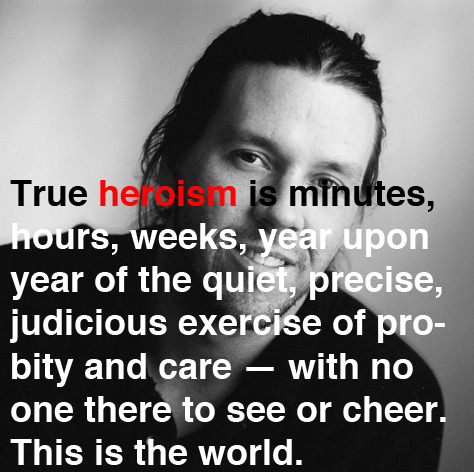

Harris’ compelling argument consists of applying a very simple question to all things we perceive as free will; “where is the freedom in that?”. Basically if we can’t account for our desires, urges, fears, and reactions, we cannot attribute what follows from them as free will. It can be a hard leap to make; I want to believe that I chose to read this book, but I can’t differentiate between what prompted me to and what would have prompted me not to. So where was I free to make a choice? Breaking it down to the simple application of a question makes the argument relevant and useful when considering what you’re subjected to in day to day life. This allows you to maintain control despite not really being ‘in control’. As Harris puts it; “you do not control the storm, you are not lost in the storm, you are the storm”.

Many people might posit that without, at the very least, the illusion of free will we might become listless or immoral. Here Harris’ job gets easier. Free will is an illusion without which we can become more aware of what we are, products of the physical world - our surroundings, our physiology, our biology, our instincts etc etc (there are infinite possibilities which I don’t doubt is why the illusion of choice laid out before us persists). By manipulating the physical world or having it manipulated for us we can still lead fulfilling lives full of awareness, understanding, and action*.

For example, let’s say you have a problem with eating too many Zebra Cakes at one time. If you imagine this is your choice and simply a matter of resisting the wrong choice (eating Zebra Cakes) and making the right choice (not) then there is no doubt you will still have a problem with Zebra Cakes. This is because you cannot control your desire for Zebra Cakes, you cannot control the chemical effect they have on you, and you cannot control your desire to want one after the other (among, again, an infinite number of possibilities beyond your control that determine your actions). There are some days that you don’t eat too many Zebra Cakes and seemingly resist the need to eat many at one time. It is here the illusion gets dangerous; you are falsely attributing any number of things beyond your control to will power. It isn’t as though you made your urge go away, it just didn’t trump, say, your fear that your wife would leave you if you didn’t kick this Zebra Cake habit, or the way your lunch digested, or an infinite of number of possibilities that simply reduced your desire or trumped it.

Ultimately it doesn’t matter, if you keep subjecting yourself to that what you desire, you’re going to give in. Every. Time.

Let’s strip the illusion away. You know beyond a doubt, despite an unexplainable good day every so often, that you are going to gorge the shit out of Zebra Cakes if they are at home whether or not you like it. You cannot make your desire for Zebra Cakes simply go away, so after reading Sam Harris’ book Free Will you realize you have to make the Zebra Cakes go away. This requires both awareness - where is your urge for the ZCs the strongest? When does it seem to diminish? What are you doing when hunger strikes? - and action; you realize you have no craving for Zebra Cakes at the store so you don’t buy them OR you do have a craving for Zebra Cakes at the store so you go to a store that doesn’t have them or you go to the store with someone who can stop you from buying them. This level of awareness and action, likely not present when you believe you can willfully make the right choice, seems to be exactly what people are afraid will disappear should the illusion of free will shatter.

(*Two side notes here: None of that was Harris’ example, he does a far better and more concise job of declawing the implications of abolishing the illusion of free will. By action I don’t mean you have free will, you’re spurred to action by your lack of belief in free will - or at least your capacity to stop eating Zebra Cakes - and/or fear and/or frustration and/or dumb luck. If you follow your action to where it came from there is no way it was free will, but hey, it’s better than just laboring under the idea things beyond your control are just going to magically disappear one day!)

Honestly the hardest thing Harris will have to contend with in his argument is writing a book people will want to read and be receptive to. Scratch that, there is really nothing he can do to make people respective to this idea, people love free will. What he can do is what he did; Harris kept the book simple, kept it very short, and he left out (apart from an absolutely chilling intro to the essay) any controversial examples. The only problem is that Harris is a controversial figure. Conservatives tend to hate him because he is an atheist or because he doesn’t believe all people on food stamps are snakes, but liberals tend to hate him because he isn’t a cultural relativist and probably comes off as islamophobic when he uses data to point out that a lot of modern Muslims think it’s still OK to throw gay people off of roofs.

Well...he tried anyway. If nothing else, and there is a lot else, Free Will is a fun read and gets you thinking. Even if you can’t follow Harris’ logic or think he sounds like a douche at times, it is still immensely important to think about free will and what we subject our subconscious to, being that it often affects our conscious actions. It is impossible to read this and think it is devoid of any truth, plus it --

You know what? Forget it. You’ll either have the urge to read Free Will or you won’t, but it isn't like you really have choice in the matter...