“Only to live, to live and live! Life, whatever it may be!” - Fyodor Dostoevsky

When it comes to climate change I have borrowed a phrase in my own writing from my good friend and climate change pragmatist Chris Powers that goes something like “Things might get bad, but I won’t be pushing my children around in a shopping cart in some Cormac McCarthy-style apocalyptic wasteland anytime soon”.

One of the things that always seemed to make the climate crisis somewhat easier to reconcile with is how far away all of the consequences seem to be from me and, since having them, from my children.

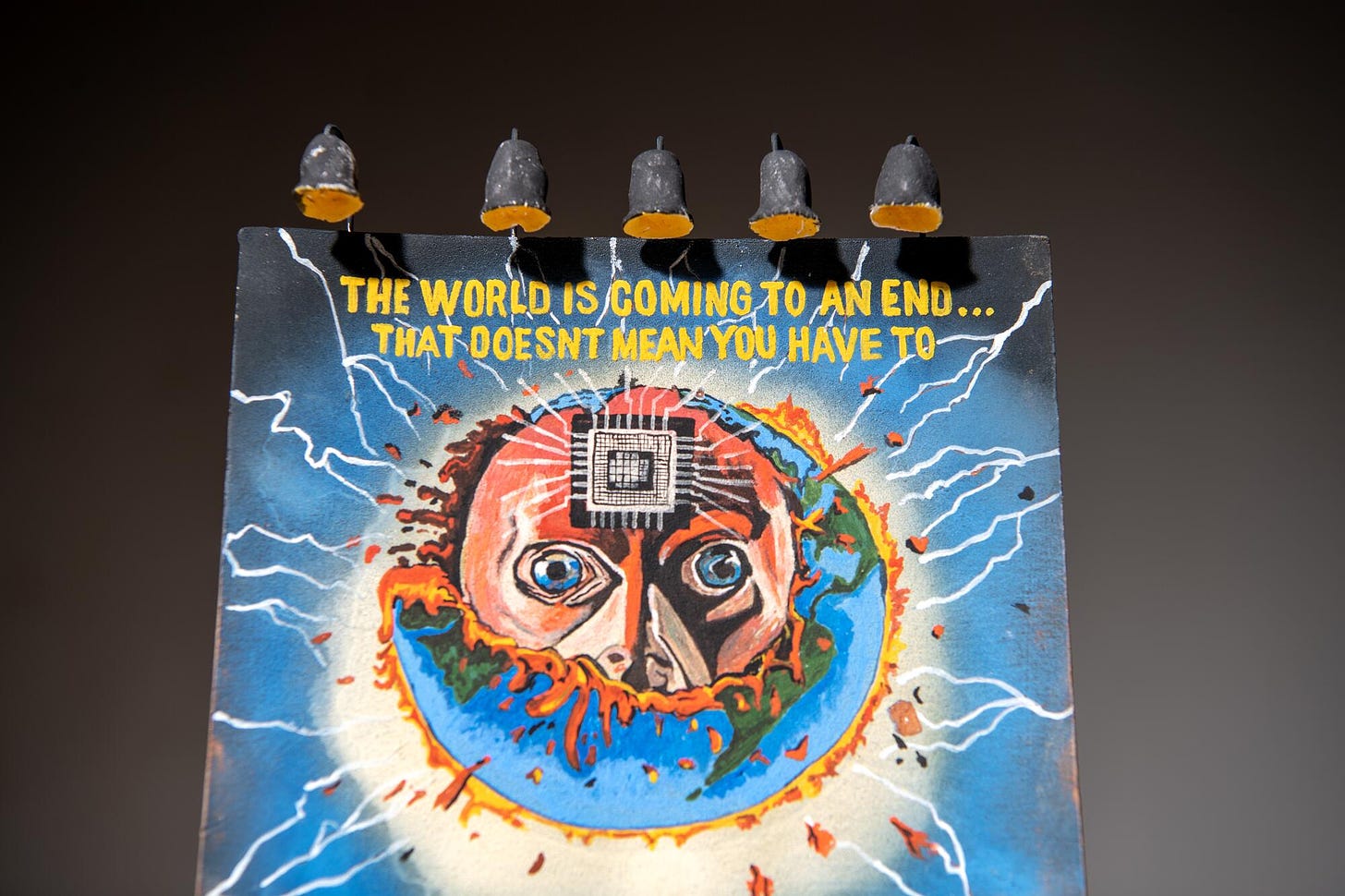

Things might get bad, I may witness some nascent systemic failures and even some far-away climate-driven atrocities, but I won’t be inflicted with the worst of it. The world will not become uninhabitable. That is until I read David Wallace-Wells book The Uninhabitable Earth where he explores the very real shopping-cart-in-wasteland-possibilities.

Wallace-Wells opens the Uninhabitable Earth explicitly and aggressively challenging the concept that the climate crisis is a distant crisis. Part one, titled only “Cascades” lays out two arguments to consider. The first is the possibility that the climate model’s predictive power is only so good and we could be in for more devastation, and sooner, than the scientific community previously thought. The second is that it is inaccurate to expect a singular, apocalyptic event to deal a final blow-style devastation, but rather cascading increments that will start to shape and change our lives, the pace of that change determined only by our efforts to mitigate damage to the planet.

In “Cascades”, Wallace-Wells contextualizes the crises in a way that feels very personal to my generation, explaining how the historic fossil-fuel burning in the Industrial Revolution “is a fable about historical villainy that acquits those of us alive today”, and that “the majority of the burning has come since the premiere of Seinfeld”, which was exactly one month before I was born. If the purpose of reading texts like these is to reconcile the climate crises with my decision to have children, the Uninhabitable Earth is essential reading; this framing brings with it an awareness that there is a cost to my life’s comfort and that is the comfort of my children.

But only possibly. Throughout the Uninhabitable Earth, we are reminded that “some climate research is speculative, projecting our best insights into the physical processes and human dynamics onto planetary conditions no human being of any age or era has ever experienced”, particularly as it pertains not to the reality of climate change but rather to the devastation it will wreak. It is inevitable that “some of these predictions will surely be falsified; that is how science proceeds. But all of our science arises from precedent, and the next era for climate change has none.”

So while we cannot know what the horizon will bring to our children or even ourselves, Wallace-Wells expects the changes to come in small cascading and interconnected phenomena that in many ways we are experiencing the very early stages of right now. He titles these the “Elements of Chaos” and each is devoted its own section in part two: heat death, hunger, drowning, wildfire, disasters no longer natural, freshwater drain, dying oceans, unbreathable air, plagues of warming, economic collapse, climate conflict, and systems [collapse].

Each “element” is expressed both as a singular possibility and as a compound with other elements. The singular possibilities are themselves compounding, sometimes taking the form of an unlikely and unconsidered phenomenon, such as the “hunger” element featuring something called “the great nutrient collapse where every leaf and every grass blade on earth makes more and more sugars as CO2 levels keep rising” thereby making food itself less filling. But hunger also ties into economic collapse, or supply chain systems collapsing, or water scarcity; themselves all their own elements as well.

This is how the climate crisis will impact us. Not through one giant disaster (although jury is not out there either), but rather death by a thousand cuts. The idea that climate change will mount some singular horrific act that will affect tragedy onto one’s personal life is rooted in individualism; it centers the person imagining the horror. In reality, climate change is a systematic change that will impact us exactly because of the interconnectedness of everything.

And in many ways, we’re seeing it already. We’ve seen fires increase their scale and damage, same with different varieties of storms. Even in my home state Michigan, sometimes marketed as some sort of climate change oasis, the winter wonderland can be made all the more deadly; “the warmer the Arctic, the more intense the blizzards in the northern latitudes - that’s what’s given the American Northeast 2010’s Snowpocalypse, 2014’s Snowmageddon” and 2016’s Snowzilla”. Just last year I watched my kids choke on wildfire smoke from Canada (wild fires and air pollution are elements of chaos explored in the book). Nowhere is safe even if they are safer than others.

Systems we have come to rely on will be pushed to the max, some already seem to be bending. And this is not some distant world of 5 degrees of warming, this is the very real, very present possibility given our trajectory; “at just two degrees, cities now home to millions would become so hot that stepping outside in summer would be a lethal risk…wildfires would burn at least four times as much land. The sea level rise would flood or down hundreds of major cities sooner, with as little as two degrees of warming.”

The Uninhabitable Earth also has very little room for optimism or any insistence that we will avoid this future, the only question is when we will endure it. Wallace-Wells beefs with everyone here; major infrastructure investment arguments of the left receive jabs about the improbability, pointing out that to avoid two or three degrees of warming we’ll need “a decarbonized economy, a perfectly renewable energy system, a reimagined system of agriculture, and perhaps even a meatless planet” when in reality “it took New York City forty-five years to build three new stops on a single subway line.”

Techno optimists and market pragmatists receive their fair share of doubt. Wallace-Wells points out the complete failure of market forces to deliver a “green energy ‘revolution’” despite “yielded productivity gains in energy and cost reductions far beyond the predictions of even the most wide-eyed optimists”. Pointing out that it “has not even bent the curve of carbon emissions downward. We are billions of dollars and thousands of dramatic breakthroughs later, precisely where we started…that is because the market has not responded to these developments by seamlessly retiring dirty energy sources and replacing them with clean ones. It has responded by simply adding the new capacity to the same system”. The market is not designed to scale down engines of profit, only to build on them.

So if we are to watch the world become uninhabitable and the only question is how fast we will watch it become so, how do you reconcile having children? I’m now cursed with the knowledge that I have brought them into a world rapidly in decline. Wallace-Wells seems to feel similarly to this as a father himself:

“I know there are horrors to come, some of which will inevitably be visited on my children…She will hit her child-rearing years around 2050, when we could have climate refugees in the many tens of millions; she will be entering old age at the close of the century, the end stage bookmark on all of our projections for warming. In between she will watch the world doing battle with a genuinely existential threat, and the people of her generation making a future of themselves, and the generations they bring into being, on this planet. And she won’t just be watching it, she will be living it - quite literally the greatest story ever told.”

It doesn’t feel particularly great starting this piece on a 70 degree day in February, after what many are deeming “the winter that wasn’t”. Yes, many of the explanations for the anomalous weather center around the El Ninio hurricane, but I just finished a book about how all the climate models could be incorrectly skewing optimistic and we could be facing an apocalyptic-level crisis in the next week or month or 12 years. The hurricane explainer might have helped me breathe easily before reading the Uninhabitable Earth, but I’m sure I will never feel that way again. It’s one of those books that curses you with a knowledge that is not forbidden, just foreboding.

There is no happy ending or optimistic lift to this piece. There was nothing like that in the Uninhabitable Earth either. Just the reality of how we will “deal” with what is to come:

”People will likely fall into spasms of panic - some of us, sometimes - considering that a future of so many more of them seems so unlivable, unconscionable, even uncontemplable today. In between, we will go about our daily business as though the crisis were not so present, enduring in a world increasingly defined by the brutality of climate change through compartmentalization and denial, by lamenting our burned-over politics and our incinerated sense of the future but only rarely connecting them to the baking of the planet, and now and again by making some progress, then patting ourselves on the back for it, though it was never enough progress, and never in time”