Monday, November 16, 2015

A ReRead of The Stranger by Albert Camus

Rereading the Stranger by Camus, it is obvious that America has hijacked Existentialism and any subsequent narratives. I see the philosophy and the narrative of the Stranger everywhere now. I watched Clerks the other day and saw countless parallels between Mersault and Dante; when describing the book to a friend who has never read it I gave into the temptation of comparing pre-existential crisis Mersault to pre-Brad Pitt Edward Norten in Fight Club; the internet is full of listicles prompting readers to live life to the fullest and not to let traditional, societal expectations prevent us from doing what we want. This all seems really existential, but I think there is something fundamentally wrong, though it is hard to put my finger on exactly what.

It seems that Hollywood and the internet respectively enjoy stoking the idea that we can't live passive lives. But their portrayal of it is missing something fundamental, something the stranger demonstrates in abundance. To Hollywood and career internet motivators, pre-existential crisis characters are boring and monotonous (think Norton's condo in Fight Club), that they are letting some triviality get in their way. They live totally unappealing lives and are usually foiled by existentially and unrealistically laid back, cooler people (Pitt from Fight Club or Randall from Clerks). On the surface, what makes this life so desirable is that it is liberating; you're free of the fetters of societal expectations. As though by removing crushing expectations we are somehow going to live happier. This all jives pretty well with existentialism, but the portrayal of what it means to live a wholesome life is still far too selfish. This idea that American mediums are spouting is still operating under the assumption that all of this is for the individual, a very American concept. Every insistence that you follow your dreams or forget what others are saying are all perpetuating, not the idea that you have to be an active participant in life, but that life is somehow meant for you.

Think about pre-existential crisis Mersualt, what makes his life so undesirable to me is his selfishness. Whether he's at his mother's funeral, hanging out with friends or loved ones, or just existing in the public, he is constantly bitching about people in his way. Not in his way like they're preventing him from following his dreams and ambitions, but in his way like their existence is preventing his existence from dragging him to his inevitable end. Or just preventing him from taking a nap and having a cigarette. In every moment Mersault is aggravatingly thinking only of his needs, of his fatigue, how uncomfortable he is, how disgusting other people are and how they are making him feel unpleasant. He lays out in great detail how pathetic is mother's old (new?) fiance looks trying to keep up with her funeral procession and how much it bothered him. The unnamed Arab man he kills (that the man is unnamed is case in point really) is preventing him from going to a shady place while he is caught in the sun. Mersault's passive life is passive because he is unthinking, because he is operating in a default setting that assumes his life is the most important one. After his existential crisis, he thinks only of others and hopes they come out to cheer his death in ecstasy. It's not like he lives a really sexy and desirable life after his revelation, he doesn't get to relive his life the way he sees fit and follows his dreams, he dies. What makes Mersault existential is not his new life in contrast to his old one, but rather his new thinking.

That's the tragedy to me; I know people who live incredibly vibrant and exciting lives that still fall in the same pitfalls Mersault falls into. That there is a sort of anti-selfishness in Existentialism that maybe entrepreneurial/capitalist America doesn't want to acknowledge. That living life as an active participant, not passive, means actively considering your life is no more important than the lives around you. Living actively, existentially, has nothing to do with people getting in your way and everything to do with your acceptance that they are there and so are you and no one is any more important than anyone. The second you attribute meaning and purpose to your life, the way American pop culture is always portraying as the only way to a fulfilling life, is the exact moment that you are living passively, taking the easy way out. It could be that Existentialism has nothing to do with living and everything to do with how you think, it is after all a philosophy.

**Read the Stranger, if you've already read it, reread it. I picked it up and a week later France gets attacked by terrorists and over a hundred of their citizens are tragically killed. They are attacked by a group of people who believe their life's purpose trumps another's. I picked it up right when protesters in Missouri with legitimate complaints of racism are considered detrimental to an individual's freedom of speech. I read this at a time where it is considered critical and intelligent thinking to assume the worst of people, to accuse those in poverty of gaming the system because of your taxes, when it is in fact the easiest possible way of thinking. Today we are plagued by those who consider their life the most important and meaningful, our country's values and pop culture are encouraging us to believe this. The Stranger is a reminder that this is man's default way of thinking and only by actively rebelling against this notion can we truly transcend.**

Wednesday, September 23, 2015

Drown by Junot Diaz

Daniel Beaty is a performance poet and artist that talks

passionately and personally about issues of race. One of his more well known

pieces is titled Duality Duel. In it, Beaty goes back and forth in two

different personas; his ivy league educated self and his street self. The two

personas are aptly named Nerd and Nigga. The Nerd flourishes stories of success

in an attempt to tell the Nigga there is no need for him any longer, but the

Nigga fires back that the Nerd is no longer relatable to his people, that he

can't fulfill his obligations to lift them up without his Nigga side. The piece

is powerful, Beaty has a goosebump evoking delivery from his projection down to

his body language. Besides that though, the piece is also smart and accessible

all at once. Beaty, using a performance poem that anyone can listen to and

engage with, isn't overly poetic on the surface at all, but on further inspection you

start to notice rhyme schemes and meter. It's also heavy in content, duality

being an altogether difficult subject to reconcile. Artists like Beaty though, are important because, just as his poem states, they make art and complex

dialogues more accessible.

This is why Junot Diaz is an important presence in

contemporary literature. The experience he comes from is both that of a black

minority and an immigrant and he is highly critical of the kind of baggage that

comes with both. His novel; the Brief and Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao, which

might as well be Duality Duel the book, won the Pulitzer prize for literature.

Before that, he published a book of short stories titled Drown. Each story,

most of which could very well be about Diaz himself, feature Yunior, Dominican

immigrant to New Jersey (see) and seem to dip into different moments of his

young and adult life. We get snapshots of him as a child in the DR waiting for

his father to send for him; to stories of him as a young man trying to date

young women; to stories of him dealing drugs on the corners in America. Aside

from two stories, one about Yunior's dad in America and the other about a

reoccurring allegorical character named Ysrael, all of these stories take place

in "the streets", both literal and metaphoric. This means they come

packed with violence, misogyny, bruiting masculinity, race and racism, drugs,

gangs, etc etc. This makes it an ideal read for most men who might not often

feel a connection with literature set in lofty White America. In fact, it

almost seems Drown is exclusively for men, Yunior is always gratingly fronting

his manhood (even as a child) and women are unabashedly objectified. That isn't

to say that women can't read the work in Drown and derive any sort of meaning,

but the book empathizes almost entirely with men.

This could strike a lot of readers as annoying. Fans of

Diaz's Oscar Wao who value its balance between "the street" and

literary endeavors might not appreciate the more subtle literary presence in

Drown, which is more frankly about manhood. This is valid criticism, Drown's

male characters are despicable to women, they're overly violent, their thought

processes are simplistically male (sex, food, more sex). Other readers though,

readers these characters are supposed to empathize with, might find them

relevant. Once those readers are hooked, that's when Diaz works in the more

complex and subtle elements. Every female character, though treated poorly, is

complex, generally strong (often physically), and have an in-depth,

multidimensional kindness. Yunior is often afraid to speak out about his run

ins with sexual abuse because he thinks he'd be perceived as weak, while he tries

to brush it off it is still evident these instances of molestation haunt him

(read: drown him). Yunior also seems to be constantly reconciling with the

cruelty of masculinity, implying that it is almost inherent in his brand. His

father and his brother seem cruel, irresponsible, inconsiderate, and sometimes

downright insidious. Yunior, often mirroring their behavior, feels what he is

doing is wrong, but also conforms to the pressure of his family and friends.

While the stories of Drown may be masked in manliness, beyond the surface there

is a delicate and emotional sub-narrative worked subtlety into each piece.

Of course one could argue subtlety working in complex themes

could mean they're willfully ignored or unintentionally unnoticed, thus

dampening the conversation they're supposed to provoke in readers who are

already hostile to these literary methods. But in Drown, the deep conversation

triggers are so haunting - fast escalating moments of intense violence, or

sexual molestation that happens excruciatingly slow - that they're impossible

to ignore. Diaz stays relevant to say, inner-city youth, but could potentially

have them questioning the intricacies of their masculine identities. Even

if he doesn't, his attempt at reaching a readership that doesn't usually feel

powerful prose is for them is a commendable effort. If nothing else, he is a

different voice in a sea of homogeneous voices speaking about tortured white

geniuses.

Monday, August 10, 2015

Book Review: Austerity by Mark Blyth

In Austerity Mark Blyth dives into what is now a very entrenched belief in American politics. Explained simply, austerity is just scaling back government spending in the form of budget cuts, privatization, and making way for private sector investments. If this sounds familiar it's because this has been the American Republican economic policy for some time now. In his book, Mark Blyth explores both the ideological history and practical applications of Austerity, as well as some brief notes about how it relates to our current crisis. The books is apparently meant to be modular too, so if any of those topics interest you, you'd be able to read one section without having read any of the others. Or so Blyth says. After reading the whole book cover to cover it is pretty obvious that not having read some sections will leave other sections less powerful since Blyth's thesis draws strength in its scope of study on the subject. For example the history of austerity as an idea and the history of its applications combine to make austerity as a concept truly inadequate in any capacity.

And this is essentially what Blyth's book says over and over; no, austerity never 'works'. By works, he means that it fails to pull a state out of economic depression over and over. Some countries like Germany can practice austerity and run a surplus, but Blyth points out that if every country did that it would be short-lived as there would be no one actually spending money. This is precisely why austerity is so dangerous; it seems to make common sense. Left, Right, Center, a lot of people regardless of political affiliation might agree that during a recession the government should spend less, should strive for surplus and growth in an attempt to pull itself out of perpetual unemployment and economic travesty. Yet, historically speaking, Blyth shows us it is impossible to cut one's way to growth. Every country that has tried to do so has either failed or forced its citizens through grotesquely long bouts of unemployment and poverty before the economy righted itself after some sort of bailout. Currently, austerity is halving practicing country's demand and subsequently growth. The more countries that practice it the worse off export and import markets become too. Wages take a hit, social programs become broken or profit driven, productivity becomes stagnant, and despite all of this the debt rarely corrects itself. Blyth explains that the ideological stance for austerity began with libertarian/anti government thinkers who, lamenting that the government was necessary if only to protect property rights, didn't want to pay for an expanding state, believing that it interferes with markets. The problem with this is that if you don't properly fund the state it won't do what it necessarily needs to do properly. It seems the reason for austerity now is that politicians are convinced that the market alone, with limited if any help from the government, will take care of itself. The problem that this book highlights is that it won't and it never has.

Blyth is fun to read in some part because he isn't a partisan extremist. He doesn't use words like "austerity jihadists" as Krugman might and he doesn't believe in some corrupt republican party agenda like mass privatization in return for kickbacks. He rather casually posits that the ideology, uses, and justification of austerity are flawed, but given its intention it remains used despite a distinct lack of results. On that same note, Blyth can get intensely over dense when talking about economic theory or history and the book has one of the biggest shit show post-scripts I've ever read. It's definitely worth picking up if you're interested, for example, in why schools historically keep getting their budgets gutted, but it might not be the most riveting thing you'll read all summer.

Tuesday, July 28, 2015

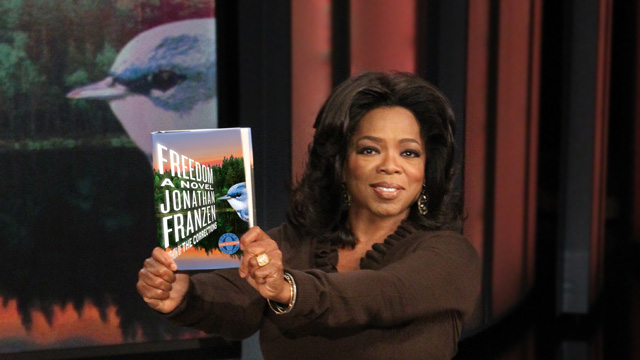

Book Review: Freedom by Jonathan Franzan

'Freedom', a Novel by Jonathan Franzen, is an incredibly fun reminder that nothing in life is ever really free. Franzen, who planned on writing a political novel about washington, turns instead to writing about families, a subject he mastered in the Corrections. He often inhabits each of his characters and gives you juicy tastes of his own eccentric political views or his take on bands like Bright Eyes. Franzen's presence here - obvious at times while not at others depending on how well you know the author - can be marginally distracting. Often times you're too consumed in the drama of whatever is inducing it to even notice. Still, Franzen evidently lives in every single character. The political opinions, often bordering that of Paul Ehrlich, can get tiresome and its eccentricity loses luster at several points. It is when Franzen is writing about the politics of family and community that he is at his best.

Here, Franzen navigates things like rape or adultery, depression or parenting, as though each event is a series of political moves. There are major pillars of political drama like crushed idealism, deceit, and the inherent injustices of democracy played out as the main female character (patty) tries not to sleep with her husband's rockstar best friend or the main male character's (walter) valiant attempts at not sleeping with his assistant. These scenes are often the most fantastic and easily consumed. They're especially fun when paired with the more experimental narrative styles Franzen uses in Freedom; the first section of the book is written from a collective POV of neighborhood gossip, the second is a memoir written by Patty herself. This way Franzen is able to layer what would otherwise be mechanical story telling into deeply personal triads into his character's psyche. In other words, he does a good job masking what he's doing. You think you're reading about family, parentings, growing up, and finding your way when you're actually reading what it means to be a cog in the human race machine.

As a result, modern politics is almost works better as a setting than a thematic endeavor. 9/11 is definitely present, but so is overpopulation, military contractors, environmentalism, neoliberalism, each political movement of the early to mid 2000's informs the narrative in new ways. Joey, Walter and Patty's son, gets caught up in a military contracting scandal, Walter tries to use environmental policy as a front for anti-growth movements. This is where the book might get tedious. There are times when Walter or Richard (his best friend) or even Franzen as narrator might start riffing on a subject for seemingly no reason; a particular unconvincing conversation between Joey and his college roommate about the Israel/Palestine conflict comes to mind. While barely thematically relevant it is even harder to draw parallels between the plot and the debate. It's easy to roll your eyes at moments like this and think "yes, we get it, too much freedom is a bad thing" or "when your freedom infringes on mine it ceases to be freedom at all". While modern politics are skillfully used, when they're bluntly applied to situations it gets flimsy in the realm of believability. Politics work better as a backdrop here, because we've already seen so much of them thematically. One could argue this is probably why Franzen went with the family as his primary thematic vehicle over Washington, he should have more consistently stuck to it.

Freedom though, is a brilliant piece of work. One of the more fun conflicts it offers is whether there is a certain level of duality in the title. While there are many artfully crafted instances of one character's freedom inhibiting another's, there is also precious little willpower. As stated earlier, crushed idealism is a staple of any political drama; think Mr. Smith Goes to Washington. It's almost laughable that these characters feel they have a choice in what they are doing. Whether they're disconnecting and cheating on their spouse or perusing something truly and utterly selfish, the reader is doubtlessly let down as that character almost unwittingly winds up doing what they were vehemently against mere seconds ago. This can be heartbreaking or hysterically funny at the drop of a dime. Franzen has you riding up and down with every character in their respective sections, feeling confident when they are and equally as devastated at their seemingly inevitable failures. Perhaps the reader too comes to inhabit Franzen's characters.

Thursday, July 23, 2015

Letter to Representative Trott Concerning Minimum Wage

Please feel free to copy, edit, paste, and send to your representative.

Representative Trott,

A major concern I have as a member of your constituency is the minimum wage. Given that you are a Republican, support the TPP, and are by no means a fan of Keynesian economic policy, I don't believe you will take any action on Senator Bernie Sanders recently introduced bill to raise the minimum wage to $15 an hour. And that is fine. But I do wish you would consider supporting legislation that raises the wage to a number you and your party deem fair.

Consider that the average number of hours worked a year is 2080 (assuming a 40 hour a week schedule). At 7.50 an hour we are looking at individuals living off $15,600 annually. After taxes - which would be the full 35% average Americans pay because the great state of Michigan has rid itself of an earned income tax credit (thanks again to your party) - you're looking at individuals earning only $10,140 a year.

Consider these aren't just teens working summer jobs. I've linked below to a study published in the New York Times that shows many individuals working on minimum wage are over the age of 25, are parents, and are most likely the head earner for their household. No family could live off 10K a year, no matter how austere. This leads to food stamps, welfare, and receiving subsidized insurance from the ACA.

Consider that your party (wrongly) blames welfare, food stamps, and the ACA for massive deficits, debt, inefficient expenditures, and everything short of ISIS I would think you would consider all avenues to limit these programs. Since you've gotten nothing but pure resistance from democrats in making massive cuts to these programs, perhaps a better - more efficient if you will - way to lessen the effects you feel (wrongly) they have on the economy would be to raise the wage, subsequently eliminating the need for such programs. You would certainly get democratic party support and, as demonstrated through history, wouldn't have to raise the wage again in the next 5 to ten years. I fail to see why you shouldn't at least give it some thought.

Raise the wage, even a little bit, it just makes sense.

As promised, my source;

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/06/10/upshot/minimum-wage.html?_r=0&abt=0002&abg=0

Representative Trott,

A major concern I have as a member of your constituency is the minimum wage. Given that you are a Republican, support the TPP, and are by no means a fan of Keynesian economic policy, I don't believe you will take any action on Senator Bernie Sanders recently introduced bill to raise the minimum wage to $15 an hour. And that is fine. But I do wish you would consider supporting legislation that raises the wage to a number you and your party deem fair.

Consider that the average number of hours worked a year is 2080 (assuming a 40 hour a week schedule). At 7.50 an hour we are looking at individuals living off $15,600 annually. After taxes - which would be the full 35% average Americans pay because the great state of Michigan has rid itself of an earned income tax credit (thanks again to your party) - you're looking at individuals earning only $10,140 a year.

Consider these aren't just teens working summer jobs. I've linked below to a study published in the New York Times that shows many individuals working on minimum wage are over the age of 25, are parents, and are most likely the head earner for their household. No family could live off 10K a year, no matter how austere. This leads to food stamps, welfare, and receiving subsidized insurance from the ACA.

Consider that your party (wrongly) blames welfare, food stamps, and the ACA for massive deficits, debt, inefficient expenditures, and everything short of ISIS I would think you would consider all avenues to limit these programs. Since you've gotten nothing but pure resistance from democrats in making massive cuts to these programs, perhaps a better - more efficient if you will - way to lessen the effects you feel (wrongly) they have on the economy would be to raise the wage, subsequently eliminating the need for such programs. You would certainly get democratic party support and, as demonstrated through history, wouldn't have to raise the wage again in the next 5 to ten years. I fail to see why you shouldn't at least give it some thought.

Raise the wage, even a little bit, it just makes sense.

As promised, my source;

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/06/10/upshot/minimum-wage.html?_r=0&abt=0002&abg=0

Friday, June 5, 2015

Book Review: Dissident Gardens by Jonathan Lethem ☭

Dissident Gardens is the tragedy of Eden played out in Sunnyside New York. "The Gardens" refers to the neighborhood in which Rose - no doubt aptly named according to her role in the garden and narrative - the central character in Lethem's novel, resides. Rose is an elderly jewish woman (though her relationship to her faith is complicated) who, in her prime, was a deeply connected member of the American communist party. She tempts all manner of characters with her radicalism, the Apple of Knowledge if an apple could have crippling expectations. We watch her daughter, her husband, her daughter's husband, her nephew, the son of her black cop lover, and her grandson, having fallen from the garden, navigate their doomed existence; doomed to dedicate their lives to bringing communism to the world of mere mortals. Dissident Gardens explores the heart of American identity one failed radical ideal at a time.

And it is a refreshing exploration. Lethem possesses a seemingly endless depth of critical knowledge about the age in which he writes. Each sentence explodes with allusions to pop culture, politics of the time, and historic events. As he hops around from generation to generation almost arbitrarily, this is even more impressive. It allows him to be witty and fun, but also poetic or genuinely engaging in dialogue at the drop of a dime. The result is an incredibly fun read; engaging, funny, and critical. The only issue I take with this is that Lethem seems to strike only one tone and some of the musings from characters he writes about at a younger age are downright implausible. Which is easily forgivable seeing as nothing Lethem has to say in this novel is anything short of stunning. Each characters tragic life is being driven forward from fear of Rose's ferocity, though the plot isn't linear, time is the only thing more ravaging than Rose. That Lethem can navigate each time period his characters are present in is an essential skill. The history of major league baseball, popular television shows, folk musicians known and unknown, all delivered with an expertise that provides a backdrop of historical realism. Each character makes a pathetic attempt at some actual event in time, whether the modern occupy movement or an episode of the Who, What, Where television game show, to springboard their communist ideology. One character releases a working man's folk record that is dwarfed by Dylan's of a similar style, another tries to start a minor baseball league called the proletariats who are dwarfed with baseball's revival on the east coast. Each artfully crafted event adds scope and context to each character, the idea being it is impossible to forge a unique identity in the midst of an American identity that is inescapable and immutable.

Historic realism in the 60's, 70's and beyond, complete with real major events, might have some people thinking Forrest Gump. Which is a good start, but instead of a bumbling single guy getting up to pee in the middle of the night and changing the course of history by accidentally discovering Watergate, you have a whole ensemble of characters dedicating their lives to what seem like painful exercises in futility, history moves without them. That's the other thing, Dissident Gardens can be incredibly sad, but not without a certain amount of didacticism. While each character tries to burst onto the American frontier waving a hammer and sicle banner big enough to make Rose proud, they ultimately fail. With the exception of Rose herself, who, though kicked out of the party officially, seems to instill this radicalism everyone is striving for into her own personal Garden of Eden; Sunnyside. It is almost as if Lethem wants his reader to walk away believing that one's politics are best lived out in their communities than debated as a lofty pillar of idealism for the nation to raise. In fact the characters who embody communism as a discourse only, are the ones who fail the hardest, it could be argued they don't even get off the ground. The others, who try to live out communism but in a rapidly anti-communist world - say Meriam (Roses daughter) and her Husband Tommy - are only marginally successful in the moment and are soon washed away by time, not even a blip on the historic radar. But this failure shouldn't sound flippant or humorous, it is truly heartbreaking. You feel excited for Tommy Gogan's record release as he and Meriam rush around making the necessary sacrifices for getting the poor man's ballads onto the music scene and you're right there with him feeling the enormous defeat in the form of Bob Dylan's raging success in doing exactly what Tommy's is doing but first....and better. Each character has this moment where, the reader with them, they are on the brink of something great and instead fall very hard and very short.

It is also important to point out that Dissident Gardens is in no way an endorsement of communism. Though that is an ideal the characters strive for, it is no reason to avoid this book. Lethem is far from pushing even the most benign liberal agenda. He likely chose communism because it really was the doomed American identity, but it is also considered adversarial to God and indeed seems to take God's place with regards to worship for many of the characters. Dissident Gardens is a very cunning novel that ties together themes like 'community over identity' with heartfelt tragic characters. Communism will be the least of your worries as you navigate the complex range of emotions Lethem will evoke. It can be as painful as watching the doomed inhabitants of the Garden of Eden try to clamber back in after their fall from grace, not realizing the garden has moved far along without them.

Friday, May 29, 2015

Book Review: End This Depression Now! by Paul Krugman

Paul Krugman is a polarizing figure in both politics and economics. Look at the comments section on any one of his many New York Times editorials and you'll see whorls of comments from ordinary conservative Americans fuming that he is "always wrong" or "a communist f***" (actual comments). Which is to say nothing of what politicians and reporters and professional political commentators say of him. And what is so wonderful about Krugman, and more importantly this book, is that what he has to say isn't incendiary or fear mongering; it isn't liberal elitism or an attack on conservatism. All Krugman is doing is rehashing Keynesian economics in our modern world, which, more simply, is just making the case for more government spending as a viable way out of the depression the US economy is currently in.

The simplicity is definitely part of what makes this book so great, but I found myself disappointed at almost every corner. ETDN is a short book, Krugman is candid and avoids getting technical, but as a result, the book avoids big conversations about economic inequality and bad economic policy. I found myself asking questions like "if there are policies (or lack thereof) that allow massive amounts of money to be pumped to the top without ever touching the bottom, will government spending really help?!"; questions I never thought were addressed, but were perfectly natural to ask. And despite his simple, almost redundant, speculations on government spending and only government spending, what he has to say is still despised. This is undoubtedly because people, not just conservatives but mostly them, have been taught to fear government spending. They are under the impression that it is fraudulent, that it isn't efficient, that inflation will raze our dollar to worthlessness and that our ever impending debt will be bought by China, who will eventually own us as a result. It is these fears that allow me to understand Krugman's tactics in writing this book and leaving out the larger, more progressive points.

Krugman attempts to gently allay all of the aforementioned fears, from inflation to excessive debt, without irony or sarcasm, and, more importantly, without a call for an onslaught of liberal policies. He is quick to point out that military spending and social security are conservative advocated government expenditures that can help stimulate the economy. He even makes a convincing case for meaningful corporate subsidies. ETDN is safe, calculating, and inclusive in what seems to be Krugman's genuine stab at talking to people who don't already listen to him. It might be hard to get your more conservative friends to read this book, but once (if ever) they do, there are an abundance of points they can take with them.

|

| Found this little gem looking for a picture of Krugman. The webpage it was found on suggests he is a Jewish Supremacist... |

Monday, April 27, 2015

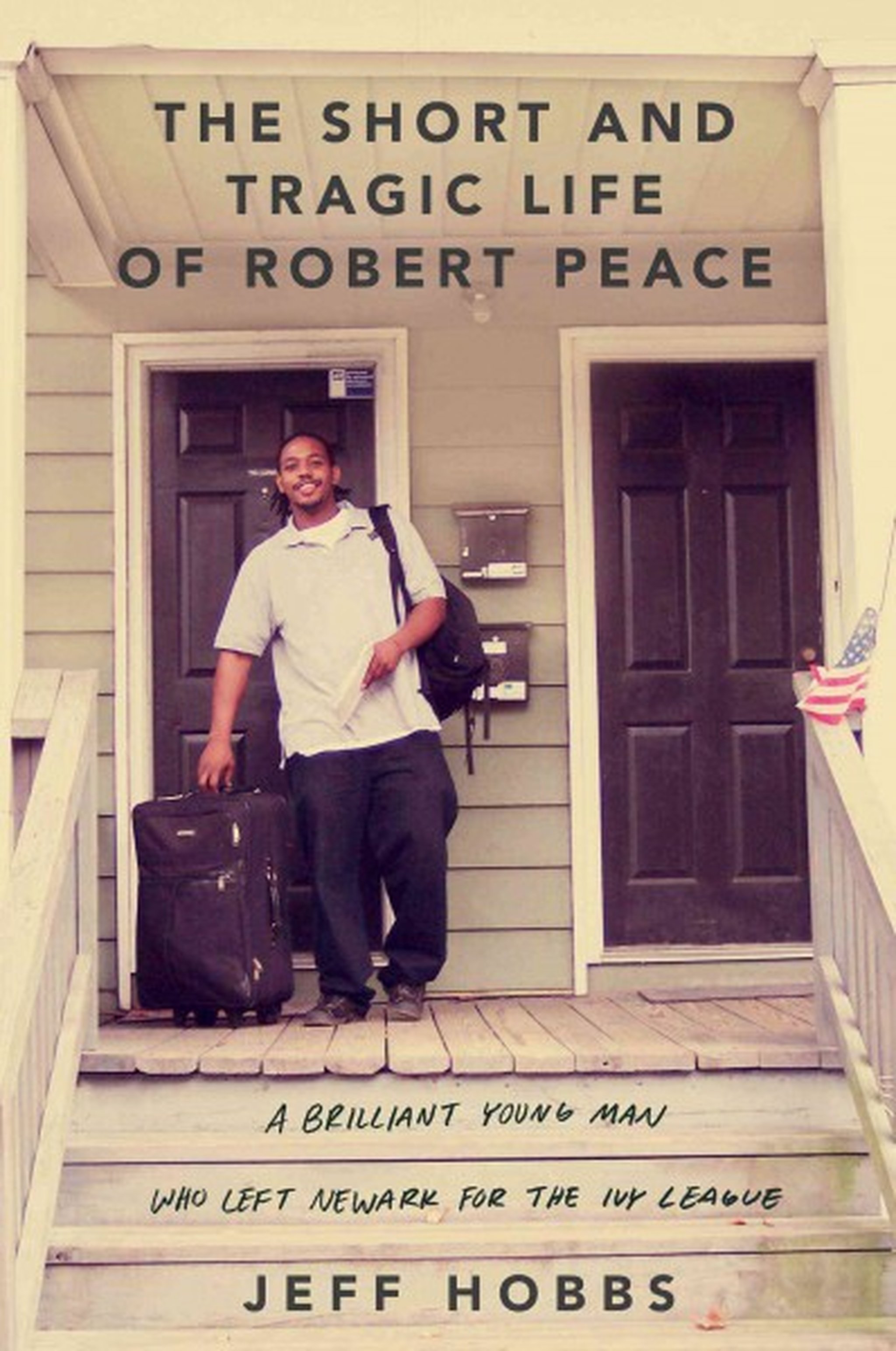

Book Review: The Short and Tragic Life of Robert Peace

At its core, The Short and Tragic Life of Robert Peace by Jeff Hobbs is an important story. A brilliant young man struggling to find his place after graduating from one of the top universities in the nation. Robert Peace runs the gauntlet of contemporary barriers for the American black man; cyclical poverty, father imprisoned for murder, plagues of gang and drug violence, racism, the education gap, and the ever-present need to "Newark proof" yourself. This last obstacle, the need to fit in within the neighborhood, is arguably what brought Peace's demise (no spoilers here, read the title). It seems to be the only thing he can't transcend as he makes his way through Yale and life thereafter. Rob Peace and the struggle he faces through this book makes it an essential read for any college student in the twenty-first century, unfortunately this takes a back seat to the author's poor attempt to play biographer for his friend he seems to know far too little about.

Outside of book clubs for moms, any adept reader might feel uncomfortable with Jeff Hobbs' attempts at describing Peace's early life. Hobbs is very evidently a stranger to the kind of neighborhood Peace grew up in. Despite his omniscient and objective narration his descriptions are amateur; referring to criminals as "dark figures in the night" or the "stupefied drug addicts" at the park. Hobbs' clear unfamiliarity with these places coupled with his impersonal and authoritative style of narration comes off as awkward, almost offensively so. There is a simple fix, Hobbs could have inserted himself in the narrative, he could have explained his unfamiliarity with these places and it would have allowed him more liberty in the way he writes. His journey to these places, his interactions with important characters in Rob's life, his visiting key locations, these all could have made the work more relatable and quite frankly, better.

This is an unfortunate major trend in the book. Hobbs' wannabe omniscient narration style that mistakenly includes things like his political views or misconceptions about life in the ghetto, dominates two narratives; that of Rob Peace and that of Hobbs himself. The book would otherwise have been able to get across important themes; that higher education is not the solution to systemic problems of poverty or the fear of how we will look when we leave where we are from and its effects on our lives. Any college student or aspiring college student could learn a lot from the struggles both Rob and Hobbs (who does insert himself fleeting in the narrative at times) face before and after Yale. The problem is that Hobbs isn't present enough for us to glean any lasting meaning from his journey in writing this book and the lack of authority he writes about Rob prevents any journey of our own in reading it.

Ultimately I think in writing this piece Jeff Hobbs demonstrates the same weaknesses as Rob, but without the lethal consequences. He is a writer posturing himself as an authority on something he clearly knows nothing about in attempt to seem almost better than the rest of his contemporaries at Yale; the stuffy and uppity students who think they are better than people like Rob. Where Rob constantly fronts himself as hard and adaptable to the streets in a way that becomes too believable, but Hobbs who offers himself as a Yalie who has seen the other side of the wealth gap and bringing it back to the rest of us privileged enough not to know it, is not believable enough. The tragedy of this book is that any importance it offers is reserved for those who have never read about or experienced that which Hobbs tries, and fails, to convey.

Outside of book clubs for moms, any adept reader might feel uncomfortable with Jeff Hobbs' attempts at describing Peace's early life. Hobbs is very evidently a stranger to the kind of neighborhood Peace grew up in. Despite his omniscient and objective narration his descriptions are amateur; referring to criminals as "dark figures in the night" or the "stupefied drug addicts" at the park. Hobbs' clear unfamiliarity with these places coupled with his impersonal and authoritative style of narration comes off as awkward, almost offensively so. There is a simple fix, Hobbs could have inserted himself in the narrative, he could have explained his unfamiliarity with these places and it would have allowed him more liberty in the way he writes. His journey to these places, his interactions with important characters in Rob's life, his visiting key locations, these all could have made the work more relatable and quite frankly, better.

This is an unfortunate major trend in the book. Hobbs' wannabe omniscient narration style that mistakenly includes things like his political views or misconceptions about life in the ghetto, dominates two narratives; that of Rob Peace and that of Hobbs himself. The book would otherwise have been able to get across important themes; that higher education is not the solution to systemic problems of poverty or the fear of how we will look when we leave where we are from and its effects on our lives. Any college student or aspiring college student could learn a lot from the struggles both Rob and Hobbs (who does insert himself fleeting in the narrative at times) face before and after Yale. The problem is that Hobbs isn't present enough for us to glean any lasting meaning from his journey in writing this book and the lack of authority he writes about Rob prevents any journey of our own in reading it.

Ultimately I think in writing this piece Jeff Hobbs demonstrates the same weaknesses as Rob, but without the lethal consequences. He is a writer posturing himself as an authority on something he clearly knows nothing about in attempt to seem almost better than the rest of his contemporaries at Yale; the stuffy and uppity students who think they are better than people like Rob. Where Rob constantly fronts himself as hard and adaptable to the streets in a way that becomes too believable, but Hobbs who offers himself as a Yalie who has seen the other side of the wealth gap and bringing it back to the rest of us privileged enough not to know it, is not believable enough. The tragedy of this book is that any importance it offers is reserved for those who have never read about or experienced that which Hobbs tries, and fails, to convey.

Friday, April 10, 2015

TV Review: American Crime

5 Episodes Deep:

Earlier this week President Obama sat down with David Simon who created the evocative show The Wire. Obama praised Simon for his work, saying that humanizing the drug war is an integral part of ending it. This is poignant and genuine commentary coming from the president. Regardless of how you feel about him he's right on two counts; the Wire was a great work of art and the conversation it was having could seriously help the way we talk about criminal justice reform. In the five episodes of the ABC show American Crime that I've seen, it is not quite the great work of art that could sit down at the same table with the Wire, but what it brings to the conversation is immensely important.

The plot revolves around several characters all linked to the brutal murder of Matthew Skokie and the subsequent assault on his wife, who at the show's start is deep in a coma. Every character introduced has a role in confusing the narrative; what starts out as "good old boy Matthew Skokie, U.S. Army Veteran (joined after 911 his mom adamantly pronounces whenever she can) and his faithful bride are senselessly gunned down by minority thugs" shortly turns into a mess of racial tension and complicated back-story. There is a lot of family melodrama the show could do without, but it adds useful context as well as some pretty powerful acting.

The archetypal roles that each character plays are, for the most part, representative of new American identities. There is a conservative hispanic father ("I came to this country the right way"), a forgotten veteran, a bi-racial couple. These crash with more classic archetypes like the white racist/delusional mother, the perfect older sibling, the rebellious teen, or the criminal illegal immigrant. This is what the show is at its core; cultures and narratives, both new and old, clashing and complicating the larger story. If at any point the viewer doubts or believes it is only because of their own preconceived notions that they bring to the show, which does a genuine job challenging them. It is constantly casting those who seek to simplify the story in a negative light. The viewer will despise the press, the prosecution and the defense, Matt Skokie's mother, but at the same time will have to constantly question if they, the viewers, are any better. There is no underlying politics to the show and it's larger point defies progressives, neo liberals, and conservatives alike; it has something to challenge everyone.

This is all delivered with same delicacy that writer John Ridley delivered in 12 Years a Slave. Nothing is shouted, everything is subtle. But what the show has in writing it severely lacks in style. Some of the younger actors have yet to come into their own; they can be painful to watch at times. Some elements are obviously added for dramatic effect; choppy scene sequencing got old after the first episode. Some characters and plot points seem to be hysterically two dimensional; that the black man accused of Matt's murder has close relatives in the Nation Of Islam comes to mind. Yet despite all of this American Crime remains an important piece of work that humanizes racial tensions in a way I have yet to see another show tackle. Anyone interested in challenging their perspective should at least give first episode a chance.

Earlier this week President Obama sat down with David Simon who created the evocative show The Wire. Obama praised Simon for his work, saying that humanizing the drug war is an integral part of ending it. This is poignant and genuine commentary coming from the president. Regardless of how you feel about him he's right on two counts; the Wire was a great work of art and the conversation it was having could seriously help the way we talk about criminal justice reform. In the five episodes of the ABC show American Crime that I've seen, it is not quite the great work of art that could sit down at the same table with the Wire, but what it brings to the conversation is immensely important.

The plot revolves around several characters all linked to the brutal murder of Matthew Skokie and the subsequent assault on his wife, who at the show's start is deep in a coma. Every character introduced has a role in confusing the narrative; what starts out as "good old boy Matthew Skokie, U.S. Army Veteran (joined after 911 his mom adamantly pronounces whenever she can) and his faithful bride are senselessly gunned down by minority thugs" shortly turns into a mess of racial tension and complicated back-story. There is a lot of family melodrama the show could do without, but it adds useful context as well as some pretty powerful acting.

The archetypal roles that each character plays are, for the most part, representative of new American identities. There is a conservative hispanic father ("I came to this country the right way"), a forgotten veteran, a bi-racial couple. These crash with more classic archetypes like the white racist/delusional mother, the perfect older sibling, the rebellious teen, or the criminal illegal immigrant. This is what the show is at its core; cultures and narratives, both new and old, clashing and complicating the larger story. If at any point the viewer doubts or believes it is only because of their own preconceived notions that they bring to the show, which does a genuine job challenging them. It is constantly casting those who seek to simplify the story in a negative light. The viewer will despise the press, the prosecution and the defense, Matt Skokie's mother, but at the same time will have to constantly question if they, the viewers, are any better. There is no underlying politics to the show and it's larger point defies progressives, neo liberals, and conservatives alike; it has something to challenge everyone.

This is all delivered with same delicacy that writer John Ridley delivered in 12 Years a Slave. Nothing is shouted, everything is subtle. But what the show has in writing it severely lacks in style. Some of the younger actors have yet to come into their own; they can be painful to watch at times. Some elements are obviously added for dramatic effect; choppy scene sequencing got old after the first episode. Some characters and plot points seem to be hysterically two dimensional; that the black man accused of Matt's murder has close relatives in the Nation Of Islam comes to mind. Yet despite all of this American Crime remains an important piece of work that humanizes racial tensions in a way I have yet to see another show tackle. Anyone interested in challenging their perspective should at least give first episode a chance.

Wednesday, March 25, 2015

Book Review: Infinite Jest by David Foster Wallace

The Infinite Jest by David Foster Wallace was a challenging book to read; it was wordy and messy; disturbing at times and nearly non-sensical at its worst. If you accept the challenge reading this book offers it will yield some truly amazing things to you, but you have to work hard. You can't just passively read this book, glazing over sections could make the entire thing not worth it. This might sound kind of snobby, in fact it will, but this is probably for the best; we should not be able to access the kind of truth DFW is offering without having to dig deep in our abilities to read, to suffer through the insufferable parts. This adds a third dimension to merging form and content that only a deeply personal author like Wallace can get away with.

One major challenge is that this book is absolutely packed with content not directly related to the main plot, picture Moby Dick with way more human element and characterization (as opposed to, you know, nautical trivia). The plot itself revolves around a staggering amount of characters. At the nucleus of this ensemble is the Incandenza family, comprised of a mother, a father and 3 sons. In true Shakespearean style, the novel picks up after the father, film maker and tennis academy founder/headmaster James Incandenza, has died after a grotesque suicide. If you are the kind of reader who reads for plot, this book definitely has a good one. James, in a distant future that sees an end to TV and a rise of film cartridges as entertainment as we know it, has created a film cartridge the content of which is irresistible to anyone who watches it. It becomes so addictive that after watching it only once, the viewer desires nothing more out of life than to watch it again and again. This cartridge is sought after by some pretty dubious crowds.

The plot, though very interesting and good, is not exactly the easiest thing to follow. It is also crowded by characters whose lives are magnified so much they become stand-ins for very dense philosophical themes. These themes are what make it all worth it. They are usually classically powerful literary themes like Shakespearean family dynamics or dystopian futures; big questions like whether free will exists or if there is such a phenomenon as too much freedom; it is all there. I mean you can find anything you want. But the themes themselves are explored genuinely and are made to seem almost vulnerable. Everything has this slight tinge of ridiculousness to it, but not ironic ridiculousness. The book, despite having almost every heavy literary theme present, focuses more on humanizing theme itself rather than lampooning it (though, some of that is there too). Wallace's cast of drug addicts, snobby teenagers, cross dressing secret agents, legitimately wheelchair bound assassins, professional athletes, disabled people, freakishly tall people, beyond logic bureaucratic bureaucrats, crazy Canadian anarchic separatists, and many more; are the various vehicles of these themes, each character with a respective back story or important tie in to the plot or setting, or just sometimes a character with seemingly no purpose at all. These are the imperfect faces of embodied literary themes.

Infinite Jest is truly unlike any book I have ever read. David Foster Wallace has such a personal style. He knows the conventions of writing so well that when he breaks them to get closer to you as a reader, maybe throwing "like" into the middle of a sentence, you can't help but be further engaged. This draws you into his acute observations about our everyday world that ring so true it can have you really feeling something, Wallace will riff on your empathy just by bringing to light something you probably have always seen but never noticed. It is these moments that truly pay off. That said, I have never been more challenged as a reader. It is too easy to see some of this riffing as Wallace jerking it to himself; the wordiness can get old; the constant tangents can lose you; there are some parts that are bound to offend you (incest is a motif in this novel). If you can get through this, if you accept the challenge, if the meaning of all of these flaws doesn't lose you; it is certainly possible to find yourself in this book.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)