While I am not a lifelong activist I’ve probably been around protests more than an average person. I have led protests and attended as a participant, I have been a liaison to the police and I have actively avoided them, I have planned protests and been a part of vehement strategy debates.

In every event, there will inevitably be a suggestion we engage in some mild level of violence. Never anything physically harmful to a human body of course, but when I led a protest against the offices of Blue Cross Blue Shield in Lansing someone suggested throwing a brick through the window, and another suggested damaging the front door to allow us inside. When I attended planning meetings for a Green New Deal protest outside of Detroit’s Auto-show Prom in response to GM’s layoffs some suggested we storm the doors, break things, and sabotage cars.

These were always a minority of voices and they were always roundly rejected. Most argue that violence is not an effective tool for protest and even if it is in the short term (IE it could get you thru a locked door), it is morally wrong and damages long-term movement building.

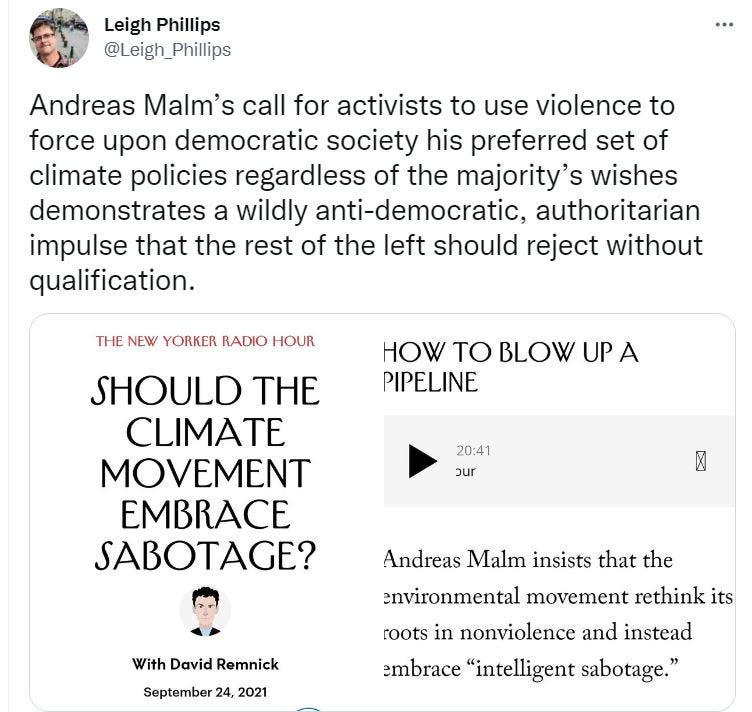

Andreas Malm seeks to turn these arguments completely on their head in his book How to Blow Up a Pipeline. Which is sort of an odd title since Malm doesn’t really offer any complex instructions about how to sabotage a pipeline, but instead takes the pacifist hard-liners in the environmental movement to task. The book would be more aptly called “Why to Blow Up a Pipeline”

To Malm, our hands are forced, we’re in self-defense mode as humans who inhabit this earth. How to Blow Up a Pipeline centers on three distinct arguments: the first is a rejection that the success of non-violent movements in the past suggests they should serve as our singular strategy in the present, the second is an argument for why widespread destruction and sabotage of private fossil-fuel property is necessarily strategic and ethical, and finally, there is a concise argument for why apathetic despair is the true movement damaging mantra.

We Love MLK, Don’t We Folks?

The first section of How to Blow Up a Pipeline is dedicated to Malm’s complete rejection of pacifism as an exclusive tactic. Realizing the bulk of the argument for non-violent resistance comes from lessons taken from successful movements of the past, Malm spends much of this section breaking these historic moments down into the sum of their more complicated parts.

Backing up a bit, Malm’s main complaint is with climate activist veterans such as Bill McKibbon whose admiral civil disobedience activities take non-violence as a mission statement. Explicitly calling on inspiration from past movements like abolition, the enfranchisement of women, and the civil rights movement these activists believe non-violence is both a “spiritual insight” and strategic in that they believe “violence committed by social movements always takes them further than their goal”.

Malm’s point that reactionary violence was a very real and very effective tool for social change rings true even with just a cursory glance at the history. The abolition of slavery is a perfect example; “slavery was not abolished by conscientious white people gently disassembling from the institution…As some recall, slavery in the US was terminated by a civil war, whose death toll still remains close to the aggregate from all other military conflicts the country has been embroiled in”. By this measure, it would seem bizarre for hardline pacifists to claim this historic moment as a win for their tactic. It would be like claiming Hitler was defeated by pacifism by ignoring the entirety of military action in WWII.

A lesser-known history is the women’s suffrage movement. Quoting extensively from historians like Diane Atkinson and her book Rise Up, Women! Malm points out that reactionary violence was so drastic it’s hard to imagine it didn’t play a role in enfranchisement; “suffragettes forcing the prime minister out of his car and dousing him with pepper, hurling a stone at the fanlight above Winston Churchill’s door, setting upon statues and paintings with hammers and axes, planting bombs on sites along the routes of royal visits, fighting policemen with staves, charging against hostile politicians with dogwhips, breaking the windows in prison cells. Such deeds went hand in hand with mass mobilization.”

Of course, the real crux of any pacifist argument is going to stem from the civil rights movement of the 1950s, 60s, and 70s. Malm acknowledges the successful non-violent strategies of the time as “the better case”. Far from being put in the corner, this is where Malm develops his actionable thesis; that singular strategy enforcement is the problem and constructively violent wings of the movement shouldn’t be condemned.

The theory drawn up is one that comes from analysis of the civil rights movement. “Radical Flank theory”, coined in the book Black Radicals and the Civil Rights Mainstream by Herbert H Haines, points out that radicalism and violence when accompanying non-violent resistance to systemic violence is more effective than either strategy on its own. As Malm puts it; “the civil rights movement won the act of 1964 because it had a radical flank that made it appear as a lesser evil in the eyes of state power”.

There were hundreds of violent riots in the late 60s, many of which leveled entire city blocks. The risk of this widespread devastation to property and human well-being was precisely what bolstered the voices of the many nonviolent protesters, quoting Haines directly; “nonviolent direct action struck at the heart of powerful political interests because it could easily turn to violence”. The double pincer of reactionary violence and strategic nonviolence is put forward as the reason for the success of the civil rights movement.

Malm concludes that “Non-Violent civil disobedience caught on because it worked - better than the alternatives, such as guerilla warfare against the state - and was appreciated precisely as a tactic, rather than as a creed or a doctrine”. After concluding that the true lesson of history is an uncomfortable embrace of violent resistance as a possibility if not at times a preferred method, Malm is ready to make his case for what to do in the face of planetary destruction.

Kill Your Local Oil Baron(‘s Stuff)

Before the second argument comes in full swing, Malm reiterates; “non-violent mass mobilization should (where possible) be the first resort, militant action the last; and no movement should voluntarily suspend the former, only give it appendages”

At long last, Malm lays out what exactly he thinks the climate movement should do:

“so here is what this movement of millions should do for a start: announce and enforce the prohibition [of new C02 emissions]. Damage and destroy new C02 emitting devices. Put them out of commission, pick them apart, demolish them, burn them, blow them up. Let the capitalists who keep on investing in the fire know that their properties will be trashed…if we can’t get a prohibition, we can impose a defacto one with our bodies and any other means necessary.”

Essentially Malm calls for widespread private property destruction, sabotage, and physical prevention of extraction. Some might argue that property destruction is not violence, but because many in the climate movement believe it to be, Malm proudly adopts the description.

This is the most controversial aspect of Malm’s work and has gotten him a lot of heat from various pundits. While the first section deals with any arguments suggesting the strategy of violence itself has always been ineffective, the second section fields arguments against the deluge of comments that claim what Malm is suggesting is immoral.

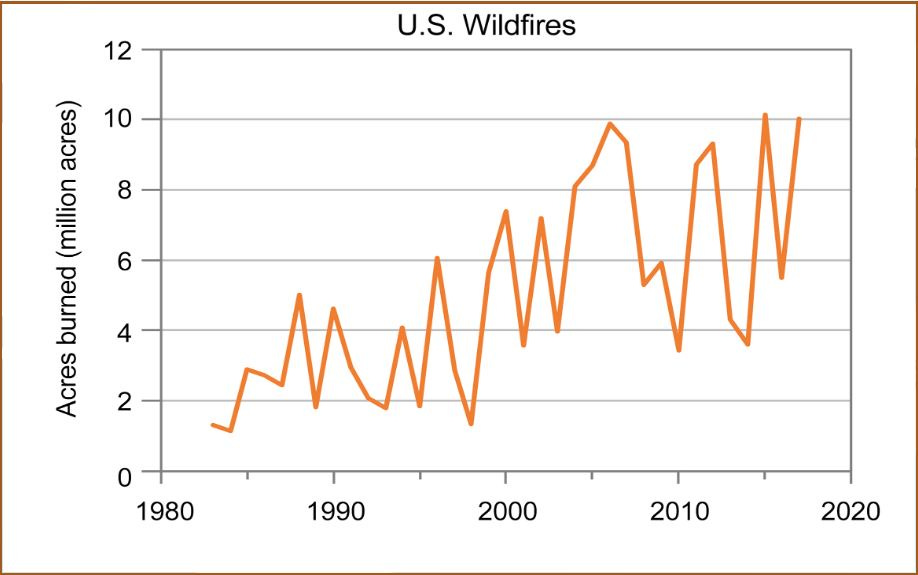

Yet Malm treats violence towards fossil fuel extraction or carbon burning property as a complex rule for self-defense. If the property was a person and was doing the same level of harm to your person and life, violent action would surely be morally justified. Since the entire planet, atmosphere, and biosphere belong to all of us, this property is in fact doing damage to, not just our personal but our life-sustaining property and we are within our right to react accordingly.

Drawing the distinction from killing - which Malm is swift to say is never justifiable as a tactic - How to Blow Up a Pipeline puts property violence on the following gradient; “one type of property destruction that approaches killing and maiming, [is] that which hits material conditions for subsistence like poisoning someone’s groundwater for drinking…at the other end of the spectrum is the blasting of a superyacht into smithereens”. Taking this logical approach means we are being killed by the owners of private property and are being chastised for damaging that property.

Imagine being shot and before the shooter can finish you off you grab the gun and destroy it. The charge leveled at you however is that you damaged the personal property of another and therefore acted immorally.

Still, violence is only justifiable, it is not always the best tactic, as Malm states over and over again. Yet there are constantly charges of violence being leveled at activists doing the property destruction, even at Malm himself for inspiring it. The charges come from all around, the property owners themselves, the brokers of the status quo like industry figures or media pundits, and even from other environmentalists in the movement.

This anger is hard to reconcile considering the scope of harm that the property itself is doing. We’re not talking about breaking the windows of a local bookstore or fire-bombing a progressive church, we’re talking about sabotaging pipelines, decommissioning coal mines, and preventing construction equipment from deforestation among other things. If we’re forced to go through the mental gymnastics of considering the property damage as violence worthy of condemnation, surely the violence the property was engaged in is far more deserving of our action.

In addition, if we as a society are truly concerned with the violence that How to Blow Up a Pipeline could be instigating, our best bet is to rapidly adopt climate and environmental policies that prevent fossil fuel and carbon-emitting property from doing much if any damage. Radical Flank Theory at work.

Never Give Up, Never Surrender!

If Malm believes there is a detrimental stance the climate movement can take its apathy. The idea expressed by modern literary figures like Jonathan Franzen is that the damage is done so we should just clutch our loved ones. Malm also seems to put those who criticize the violence of the radical flank in this same bucket.

If strategic pacifists argue that we’re not at the point where widespread sabotage is warranted, they’re really no different than the fatalist who claims the damage is done and activism is useless. To Malm' “Fatalism of the present holds defeated struggles of the past in contempt, and so does strategic pacifism: if someone raised a weapon and lost, it was because she raised that weapon…In the universe of strategic pacifism, only the winners deserve praise”.

So while the hardline pacifists of the movement claim, with some validity, that violence does damage to the movement as a whole, Malm would argue that this unpopularity can be weaponized rather than allowed to turn the movement into something the public despises.

Malm understands that violence is not for everyone and even seems to relent that the majority of the climate movement will not necessarily participate in hostile engagements with law enforcement. However, should the activities of the radical flank arouse public condemnation, the strategy is for the less radical, bureaucratic arm of the movement to leverage the moment for systemic change.

This is where Malm seems to lose the thread. There is no question that violence, even if we can make an air-tight case for its heroic justification, is going to draw criticism and unpopularity towards the movement. Charges of terrorism have been leveled at eco-activists engaged in this work before and we must never forget that the government has a powerful War on Terror propaganda apparatus that can quickly be adapted (something Malm seems to forget as much of his movement focus is out in Europe where beat cops aren’t even armed). Malm is correct to justify violence against property destroying the earth, but the inspirational and/or deleterious effects on the movement are impossible to determine.

Even if you’re not going to drop your protest sign in favor of a monkey wrench, even if the idea of destroying something that isn’t yours, even something that is itself incredibly destructive and destroying everything you love, there is no disagreeing with Malm that the fight matters and we all need to be engaged in it somewhere:

“The alpha and omega of the science of the cumulative character of climate change run contrary to the axioms of fatalism. Every gigaton matters, every single plant and terminal and pipeline and SUV and superyacht makes a difference to the aggregate damage done.”